#

The 49 men who successfully enlisted from Olive Street are but drop in the bucket of the total Australians who went to war between 1914 and 1919. Official statistics state that around 420,000 people enlisted from a nation of 4.9 million; around 38.7% of all men aged between 18 and 44 at the time. From Western Australia, more than 32,000 men went to war.

Olive Street represents only 0.01% of the national total, just 0.15% of the state total, and around 2.5% of the 2000+ Subiaco men I predict will feature in the Landscape of Loss study over the next three years. So, the statistical data gathered through this study is of little immediate relevance to the national context, or even the wider local context, taken as it is. The sample is too small to draw any strong conclusions of relevance to anywhere but Olive Street itself.

And therein lies the value of the study. While it may be a small portion of the overall whole, the numbers here represent as many Olive Street soldiers as possible. The representation for the street itself should be somewhere near 100%, which provides quite a comprehensive picture of the war experience of these residents. In time, as additional streets are investigated, a picture will begin to build of the impact of war on one complete suburb of Perth.

The information used to generate the statistics below has been collected from a wide range of primary resources, including WWI service records, Births Deaths and Marriages records, cemetery records, newspaper family notices, and so on.

Age at Enlistment

The average age of enlistment for Olive Street soldiers was 27.5 years of age, and recruits in the street ranged from 18 through to 52 years of age.

A number of people over the years have investigated and detailed the age

ranges of recruits to the First Australian Imperial Force, including

Bean, Robson and McQuilton.

McQuilton provides a clear table of the statistical analysis of age

ranges in Robson's work, and the Olive Street percentages (shown also in

the chart below) are provided for comparison:

Most of the numbers match the standard seen across Australia during that time period. The major point of interest in Olive Street is the comparatively high enlistment (double the usual statistic) of men over the age of 40.

Seven different men aged 40 and above went to war from this road, including the oldest- 52 year old Nicholas Durkin- who lied about his age to enlist. That represents 14% of total enlistments from the street.

In terms of family situation, five of the seven men were married, most with children, which is a significantly different proportion to any other age group in the study. Five (including one unmarried) enlisted after close relatives- sons or sons-in-law, younger brothers, or nephews- went to war. One of the men, John Christian Monson, was the only man in the street listed as legally separated from his wife, and a great deal of public conflict had occurred within the family in the years before he enlisted (see Marital Status, below). Others, such as Nicholas Durkin and John Mackie, had also been in the news for marital problems prior to enlisting.

Six of the seven men were engaged in heavy physical work at home, including mining, railway construction and carpentry, and no doubt felt their experience and physical capacity would be as valued on the front as it was in their regular occupation.

Two were declared unfit (due to advanced age) before they saw any service. Two were killed, and the other three all returned to Australia wounded or ill. One, Ernest Sampford, died only a few years after the war in the Edward Millen Home in Victoria Park, which treated soldiers who suffered, as he did, from ongoing respiratory problems.

The youngest man to successfully enlist on Olive Street was Eric Armstrong Simons, of number 84. In February 1917, his parents signed permission for him to go to war, swearing that he was 18 years and 4 months of age. However, Eric was actually only 17 years and 10 months of age. He'd been a keen cadet in the 87th Infantry Citizen Forces for four years, and was well-known around camp, so he didn't get away with it.

By the time he arrived in England to join the training camp, the war was coming to a close, and he saw no active service, instead being attached to the AIF Headquarters in London until late 1919. Simons presents as a fiercely motivated individual, who started as a junior clerk in the Lands and Surveys department at 16 years of age. After the war, he and his wife Kathleen, who he married when he was still only 18, moved out to Serpentine to become settlers on the land. By the 1930s, they had returned to Victoria Park, where Simons worked again as a clerk.

When the Second World War began, he was 40 years of age and a father of nine, and he was straight in line to participate, joining the 10th Garrison Battalion on 9th October 1939. He served as the quartermaster and adjutant of the Northam training camp in 1940 before transferring to Perth Headquarters, rising to the rank of Captain by 1945. After some time working to oversee prisoners-of-war, he travelled overseas again in 1946 as a guard transferring released Italians back to their homeland.

Marital Status

Around 63% of Olive Street soldiers were single, and 33% were married.

One soldier, John Monson, had legally separated from his wife Laura after a tumultuous few years that included bankruptcy and the loss of a child. Monson listed his eldest son Kelvin as his next of kin at the family's Barker Road home. Kelvin was aged just 13 in 1916 when he received the news that his father had died of wounds received at Pozieres.

Over the following years, Laura worked independently as a typist to support herself and her four younger children, eventually reaching a stage where she was able to buy her own property in what is now Perth's London Court. They stayed in the house on Olive Street until 1922, becoming some of the longest remaining residents from the First World War years. There was a large movement of people in the years following the war, with very few Olive Street residents remaining in the same homes beyond 1920.

Kelvin Monson fell in with a bad crowd and turned to a life of crime, becoming something of a celebrated burglar in Perth, known not only for his crimes but for his good looks and smart wardrobe. His notoriety grew to nation-wide status in 1926 after he escaped the famous Pentridge Gaol in Melbourne, managing to evade searchers for several weeks by stowing away on a ship to Fremantle, where he was eventually re-captured.

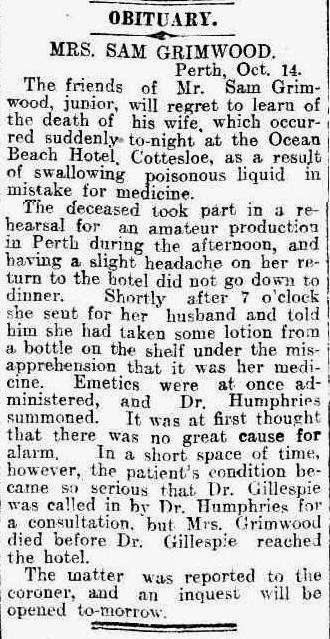

Another soldier, Samuel Edward Byrne Grimwood, was a widower- his wife Mabel had died tragically from an accidental poisoning at Cottesloe's Ocean Beach Hotel in 1912, mistaking his Lysol-laden hair tonic for her headache preparation. In 1918, after a period of time commanding the 10th Light Horse regiment in the Middle East, Grimwood married Florence Mary Duder in Egypt, and they returned home and settled down to new life in Western Australia.

Occupations

Olive Street residents were employed in a wide range of occupations, some of them very manual in nature, and others more professional. While a range of occupations was evident all throughout the street, there was a higher proportion of professional workers living at the southern/ Bagot Road end, and a larger number of manual workers at the northern/ Hay Street end. This accords with impressions of Subiaco at the time, in which those homes in the south of the suburb were "characteristically larger and more expensive." (Spillman (1985), pg. 177). Spillman goes on to note that:

By 1911, the contrast between the residential areas south and north of Bagot Road was perceptible enough for 'Vindex', the aggrieved letter writer of the time presumably resident in the north, to write:

The most common professions were Clerks (almost 20%) and Labourers (16%). The street also included three miners, three people working in tailoring, four people working in farming or on stations (and others with country associations), and two carpenters. Representing government workers, there was a postal official, a telegraphist, a policeman, and a civil servant from the Lands Department. On the professional side of things, the street included an accountant, a sharebroker and a bank officer, as well as a dentist. A saddler, a harnessmaker and a horse driver showed the continued importance of horse-drawn transport in Perth at the time.The upper portion of Subiaco - mostly occupied by villas... is well cared for, but the lower thoroughfares - those from Bagot Road to the railway station - are in a state that beggars all description.

Several of the labourers worked in the Goldfields, or on the Trans-Australian railway construction that was taking place at the time. Many of them listed Olive Street as their permanent residence while working many hundreds of kilometres away, perhaps indicating an early version of the Fly-In, Fly-Out work so common in Western Australia's resources industry today. In most cases, a parent or other relative continued to live at the Olive Street address, creating a home base to which they could always return. This would continue to be the case for many who went to war.

Place of Birth

Spillman (1985, pg. 87) writes that,

A typical Subiaco family during this period [c. 1898]... probably hailed from Victoria and very likely consisted of a youngish couple and several small children.Some fifteen to twenty years later, many of those small children had grown into men, and they were amongst those to enlist in the First World War.

Statistics around the place of birth of Olive Street soldiers show that Victoria was overwhelmingly the largest single origin point of men enlisting in this street- some 40% had been born in that state, with a large number of others also coming from New South Wales, and others from even farther afield in England and Ireland.

Only 12 had been born in Western Australia, and just one single Olive Street soldier identified as having been born in Subiaco itself- John Wilson Menagh (Jnr), whose father (who also enlisted) had been Victorian-born.

Religion

The majority of Olive Street soldiers identified as followers of the Church of England, with large numbers also following the Presbyterian and Roman Catholic faiths. Single soldiers were Methodist, Wesleyan, Congregational, Church of Christ, and Jewish.

The only Jewish soldier on Olive Street, Leopold Gluck, was the eldest son of Harriet and Albert Gluck, and the family had lived at the house called "Mirrojen" on the corner of Barker Road and Olive Street since 1910.

Leopold Joel Gluck (11Bn)

In 1911, Albert Gluck passed away, and over the following years the other children of the family moved out to make their own homes. When Leopold enlisted in 1914, it was just he and Harriet still living on the corner of Olive Street, and after he departed with the 11th Battalion, she moved in with another brother in Mt. Lawley.

Leopold Gluck was killed at Gallipoli on May 2nd 1915, in particularly harsh circumstances described by a friend:

"Gluck went to sleep one day having a rest, and while in that position he was shot through the head. He never woke again."

(Private Myslis in The Sunday Times, 31st October 1915)

Height and Weight

There was a wide range of physical stature evident up and down Olive Street, with heights ranging from 5'4.25" (163.2cm) to 6'2" (187.96cm), and weights ranging from 49kg (108lb) to 92kg (203lb). The average height of Olive Street soldiers was 5'8" (172.7cm), and the average weight was 65kg (143lb).

The shortest man on the street was James Rogers, of number 23, who was a 20-year-old horse driver. He was not the lightest, though- that dubious honour belonged to 18-year-old tailor's cutter Robert Hutchinson, of number 85, who made it through the enlistment process only to be discharged for "poor physique".

James Rogers, the shortest man on Olive Street

The tallest man associated with the street was Charles William Grimwood at 6'2", and the heaviest man was his brother, Samuel Edward Byrne Grimwood, who was just a shade shorter at 6'1 1/2", and weighed in at 203lb (92kg). Sam Grimwood was a large person in all respects- his resting chest measurement of 41.5" was 1.5" greater than the fully expanded chest measurement of the next nearest man.

Portrait of Grimwood (may be Sam or Charlie), 7th May 1917

Sam Grimwood was also a character who, like his father before him, was well-known in Perth's sporting circles. Grimwood had spent his entire life around horses, with his father having been a Melbourne Cup jockey in the early years of the race. At the time of his enlistment in 1914, he was a sharebroker and a partner in a finance firm, and also Stipendiary Steward in charge of the WA Turf Club's races. He rose rapidly from 2nd Lieutenant in the 10th Light Horse to become a Captain, and then a Major, and in 1917 was for two months Lieutenant-Colonel in command of the entire regiment.

Lt-Col Todd addresses the 10th Light Horse (Sam Grimwood on far left) in Egypt in 1917

Grimwood was seriously wounded on numerous occasions, suffering gunshot and shrapnel wounds to each knee in separate incidents at Gallipoli, and he was ill many times, including a bout of appendicitis that required surgery. His large stature and physical strength seem to have been an advantage throughout, and he must have been quite a formidable person.

Interestingly, in addition to the Grimwood brothers, there were four other men in Olive Street who served with the legendary 10th Light Horse regiment. Combined, their average height was closer to 5'10". This is going to be an interesting statistic to watch as additional information is gathered about the full cohort of Subiaco soldiers- were 10th Light Horse soldiers physically different to the rest of the Western Australian battalions? Were there any other patterns across battalions? How did changes in the enlistment standards affect the averages in different years?

Outcomes

New studies have recently suggested that the official casualty numbers for Australian troops in the First World War are not quite accurate, recording far too few injuries and falling short on deaths.

Nonetheless, the numbers provided by official sources show that of those Australians who went to war, around 60,000 died, and a further 155,000 were wounded in action. From 420,000 enlistments, over 430,000 instances of illness were recorded, demonstrating the tough time that Australian troops had with disease.

The official percentages equate to 14% loss of life, or 3 in every 20. 35%, or an additional seven in every twenty, were wounded. This gives a casualty rate of around 50%, or one in five, not including illness and non-battle injury.

In Olive Street, the war losses were significantly higher than average. 37%, or almost four in ten (a total of 18 people), died during the war, with several others passing away within a few years of their return. 39%, another four in ten (19 people), were invalided or discharged early, which includes wounding, illness and general lack of fitness for service (poor physique and advanced age being two of the many reasons given). Only two in every ten men returned home after 1919 in relatively fair health.

Examining the service records, though, shows that only four of 49 men who embarked for war were never ill, injured, or died. Two of those were discharged and returned early because of age. Two were seconded immediately into work in London, and never saw active service. All of those who made it as far as the frontlines were therefore injured, ill, or died at some point in their service.

The Gallipoli Dead- and the rest

One aim of this study is to look at the bigger picture of the impact of war in Subiaco, and that includes understanding which parts of the war most affected the population.

Today's commemorations centre heavily on Gallipoli, and as the first moment of conflict for many young Australians, there is no doubting the significance, nor the lasting effect it had. Many of the subsequent impacts of the Western Front were likely still tied to Gallipoli for those who enlisted after hearing of family or friends wounded or killed in Turkey, or for those who had served and survived.

However, in examining these records, it has become quite clear that other moments in time had an even greater impact on Olive Street than the first year of Australia's war.

Statistically speaking, of the 49 soldiers who enlisted from Olive Street:

11 (20%, or 1 in 5) fought at Gallipoli

Only 2 (4%) were killed there- Leopold Joel Gluck, and Thomas Edward Byrne

Of the 9 who survived, 3 more were subsequently killed in action on the Western Front.

By contrast, 16 (32%, or 1 in 3) were killed in action or died of wounds received in France and Belgium. More soldiers died on the Western Front than the total number of those who served at Gallipoli, and the death toll was eight times greater over the subsequent three years.

Olive Street's Darkest Days

By far the greatest impact was seen in the three months from July to September 1916.

The battles at

Fromelles and Pozieres were Australia’s first experience of the Western Front.

Between 19- 20 July 1916, an estimated 5,500 Australians were killed or wounded

at Fromelles, described as "the worst 24 hours in Australian history". A few days later the Battle of Pozieres began, extending through

to the Battle of Mouquet Farm. Between 23 July and 26 September, over 23,000 Australian men were killed or wounded.

During those

terrible months, five Olive Street soldiers were killed in action, and five

were seriously wounded. Those ten casualties represented 20% of enlisted

soldiers for the street.

Pozieres after artillery bombardment, August 1916

Long after the evacuation at Gallipoli was complete, Olive Street soldiers and their next-of-kin continued to suffer losses. More detail on some of their stories is provided in the next post, Olive Street Stories.

.jpg)

.png)

You're research is amazing and extremely important to understanding the effects of war. Claire, you're an excellent historian!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Zan Marie :)

DeleteI agree!

ReplyDeleteAlso, some of the numbers are fascinating. If only close to 40% of eligible men enlisted, that goes to show how many were needed on the farms back home. And the average was 27? That seems old - old enough to have connections that were difficult to leave behind and old enough not to be as naive about where they were headed as boys of 18 might have been, and therefore their stories are all the more poignant.

Each individual is interesting - what of those two seconded to work in London, does that mean they might have done espionage work?

Hi Deniz- not quite as interesting as all that, I'm afraid :) One worked in administration for the Australian High Commissioner, receiving and responding to correspondence etc; the other was attached to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, assisting with processing soldiers' money. Absolutely no hint of espionage to either of them :)

DeleteThe age average is pulled upward by the comparatively high number of men who enlisted over the age of 40- and, their connections were the reason they went rather than a reason to stay. Most were following younger relatives across. Of the rest, many were still single at that average age- some of whom had spent most of their adult lives working in very remote mining areas with few eligible women around.

And, lastly- very few of these people were associated with farms, though a couple were. This is very much an inner-city suburb of the capital city of the state. Those who stayed behind were in many cases rejected for service (for reasons of flat feet, poor eyesight, existing health issues such as hernia etc), were at the very bottom or top end of the age requirements (and some were probably unfit as a result- the physical testing was quite intense!), and others were still required to keep businesses running in the city- looking at the range of occupations shows the range of businesses that depended on manpower. It wasn't until the Second World War that women were more easily able to take on some of those roles. In an area like this with a high concentration of working class labourers, the only people considered suitable to keep the foundries and the mills operating were men of enlistment age.

Lots of factors behind the patterns! :)

Lots of factors, indeed. Thanks for the additional details!

ReplyDeleteNo worries! Thanks for the thoughtful comments :)

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteLooking for high-quality dental jackets and dental uniforms in Perth? Our premium collection is designed to offer comfort, durability, and a professional appearance for dental professionals. Whether you're a dentist, hygienist, or dental assistant, we provide uniforms that meet the highest standards in both style and functionality.

ReplyDeleteOur dental uniforms Perth range features breathable fabrics, modern cuts, and easy-care materials that keep you looking sharp all day. From sleek Dental Jackets to complete sets, we cater to both men and women working in clinical environments.

With fast shipping across Perth and Australia, upgrading your dental wardrobe has never been easier. Choose confidence, choose comfort—choose uniforms that reflect your professionalism. Shop now and elevate your team’s appearance with our trusted dental wear solutions.

this is so factual

ReplyDelete