Last week I attended my first Australian Historical Association conference, held this year in the historic Victorian goldfields town of Ballarat.

In my previous work I've been to many archaeology conferences, but this was my first time joining the crowd as an outright historian. Ultimately, a fabulous experience in every way. The four-day conference was jam packed from beginning to end, with almost a dozen concurrent streams in some sessions, plus a plenary each day.

While this breadth of material was initially a little bit hard to navigate, there was always something fascinating to choose from. As a result, I came home with a whole range of new ideas and a great surge of enthusiasm for my own work. I met so many lovely people with so many great projects- there's just nothing like being surrounded by a whole lot of similar minds, occupied with similar topics. A great festival of history.

I attended papers in all but a couple of sessions, so I'll split my record across a few posts to save it from becoming too overwhelming.

Ballarat welcomed us with some stubbornly cold, grey and drizzly

weather that would persist for the whole week. The temperature did not

go beyond 9C most days, and the sky barely stopped spitting for five

minutes at a stretch. Given that the conference was spread across three

separate venues up and down Lydiard Street, requiring a bit of a hike between each, this was not

the ideal weather. Nonetheless, suitably rugged up and umbrella-fortified, everyone took

to the streets with a cheerful attitude.

The coffee and hot chocolate

sector in Ballarat must have experienced quite the surge in business! Appropriate for the theme of the conference- From Boom to Bust, which was interpreted in many different ways across many different topics.

Day One- Tuesday 5th July

After a welcome reception at the Ballarat Art Gallery the previous

evening, the conference kicked off at the beautiful 1859 Ballaarat Mechanics' Institute building on Tuesday morning with a plenary

lecture by Adam Wilkinson.

Adam had travelled across the globe from Edinburgh

to talk about urban conservation, and the importance of recognising the

present, lived value of heritage places as much as we recognise their past value. He had

many fascinating examples of the way Edinburgh has revitalised the use

of historic locations within the city in innovative ways, thereby

increasing their value to the community now, and ensuring a greater

level of ongoing protection.

It was a lively and interesting plenary

that set a great tone for the whole week, and a perfect subject for a place like Ballarat, where heritage is on display on every corner. There are some great initiatives in town to help people explore the history of the place, including the Ballarat Revealed app, which can be used as a sort of walking tour through your smartphone.

Most tea breaks and lunches took place in the Hummfray Room of the Mechanics' Institute, which was a bit squishy for (so I hear) close to 400 delegates, particularly when book launches were also held at those times. However, it certainly did lend itself to meeting new people- I really enjoyed all the chats I had with others from universities and institutions across Australia.

Day 1- Session 2

After morning tea, I walked up to the School of Mines to attend the session on Vietnam, Uncle Sam and the Peace Movement. This is not an area of history I've worked on much myself, but I'm growing interested in it for several reasons. First, because I have relatives who were closely involved in the Vietnam protest movement. Second, because I now have family connections to Vietnam itself. And third, because working on First World War history over the last few years, I've been a keen observer of the trends in Anzac attention, and I have perceived a very interesting shift toward the Vietnam War as an area of historical focus into the future.

The three papers were all fascinating, particularly given the presence in the room of several people who had been directly involved in the events discussed, who were able to give great insight into the time.

In discussing the anti-Vietnam War protests, Lisa Milner talked first about the role of women's organisations, and in particular the work of Freda Brown, a fascinating figure who has been a little sidelined in this area of history. You can read some of Lisa's work on Freda Brown here- her story is very worthy of being heard.

Nicholas Butler spoke next, detailing how anger over the 1967 execution of Ronald Ryan, the last man hanged in Melbourne, rolled into subsequent radical protests against the Vietnam War. This review of the play Remember Ronald Ryan details some of the same historical background, explaining how the two events came to be related in a time of major social upheaval for Melbourne's youth.

Both papers gave a unique angle on the tensions of the time, and reminded that Australia has a strong history of people standing up to protest when necessary.

The final paper in the session was given by Holly Wilson, who spoke about protests that took place in Sicily in 1997 after many jobs were cut at the NATO/ American military base at Sigonella. This was quite a different geographic and cultural context, particularly given that the protesters were arguing not against war, but against the loss of work. A very interesting counterpoint.

Day 1- Session 3

After lunch, I wandered back to the other end of town to attend a session at the Camp Street building on Photographic Histories. Not only have I done a lot of work with historic photographs in my years of cultural information management, but I have a large collection of my own family's material that I'm still working through.

The first paper was presented by Fiona Kinsey and Hannah Perkins from Museum Victoria, talking about a true boom and bust tale- the 120-year rise and fall of Kodak Australasia, as seen through oral and visual records. Starting as a local company before merging with the larger international brand, Kodak Australasia experienced great growth and success through the middle part of the 20th century- only to decline and fall just as quickly as the digital era swept into photography in the 21st century. The visual record provides such an interesting illustration of the story.

The second paper was given by Heatheranne Bullen in what had to be the most heroic performance of the conference. Just at the end of the previous paper, the AV system dropped out- and could not be revived. Presenting in a tightly-framed session, giving a paper that relied almost entirely on the visual elements, it was enough to make anyone shudder. But Heatheranne soldiered on like a champion while the venue staff scurried to get the screen working again, presenting probably half her paper before the technical issue was fixed. Despite the lack of visuals she did a stellar job of describing the unseen photographs she was discussing, and I know we were all relieved for her when at last the problem was fixed.

Her paper discussed a collection of family photographs taken around Oodnadatta in South Australia in the 1920s, exploring what could be learned from the visual record. It was easily one of my favourite presentations of the conference, looking not only at the obvious, but also at the importance of the context we cannot gain without talking to other people. There have been many additions to the understanding of these photographs through Heatheranne talking to people who still live in the area, or who do similar work today. Heatheranne also overlaid modern and past photographs to demonstrate landscapes that had changed or had not, and looked at the importance of perspective in photography and interpretation. Just great.

The final paper was an emotional hard-hitter, with Jacqueline Wilson talking about the visual representation of boat people over the past decade, and the political uses of those images. I find some of those photographs very hard to look at, but it was a very timely and important topic, and well covered.

Day 1- Session 4

The final session of Day 1 was one of the most interesting I attended. The topic was, The Fortunes of Women? Life, death, and loss in reproduction in Australia, 1850- 1970.

Madonna Grehan spoke first with a searing and insightful view of childbirth at home gone terribly wrong between 1850 and 1880. As a midwife and nurse herself (as well as an historian), Madonna takes an unflinchingly political view of the history, intending to use it to eliminate some of the romantic ideals she believes are held by many modern home birth advocates. In the cases she discussed, there was nothing romantic about the desperate ends met by many women delivering their babies at home. The comprehensive stories of death by haemorrhage in particular were truly horrifying. The paper sparked some lively debate between presenter and audience, and I'm sure everyone was left with much to think about.

The next speaker was Dot Wickham, talking about the Ballarat Female Refuge, where unmarried mothers were 'incarcerated' in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was another fascinating piece of history, though I did find myself questioning some of the conclusions, in particular the interpretation of tone (terse vs compassionate) in the comments of the doctors on official records. I'm sure a shift in tone is evident if you read through many years of records, but in the examples given, I saw the same kind of comment that is evident in the daily records many of the other institutions I've studied, such as police and lock-up records, native welfare, and the military. There are certainly subtle hints of tone there (exasperation being high on the list!), but a definite interpretation of that seems a tricky prospect in the absence of other evidence to support particular attitudes. Which of course, may exist- I would be interested to learn more about this, because it was a great subject, and one that, as Dot explained, comes with a lot of silence around those female perspectives. I love that so many projects are working to find some noise amidst all the quiet, and to fill in gaps that have long existed in the historical record.

The final speaker was Judith Godden, talking about the Crown Street hospital in Sydney, and the forced adoptions of the 1960s and 1970s. This is a topic that has directly affected a family friend, and the details of women being coerced into giving up their babies were pretty harrowing in places. Also very interesting to see the adoption bust that occurred as social change accelerated (post-birth control) and more support was made available for single mothers.

It really was a fascinating session, with the topic of motherhood always so fraught with emotion, particularly in relation to past troubles around maternal mortality, moral judgement of single mothers, and adoption, particularly forced removal of children. I thought all the speakers navigated their topics with sensitivity, and the passion in the room was a good thing in collective total.

Worn out from a long day of listening and learning, I didn't attend the evening events, but rather went back to my hotel to prepare for giving my paper the next day. I'll add a detailed post about that, too, and I'll continue to blog about each day of the conference, updating with links below as I go.

The Road to War and Back

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

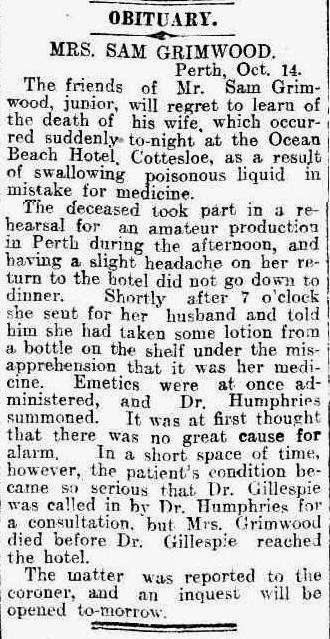

Friday, October 30, 2015

2014 Centenary Events: Blackboy Hill and Fremantle Troop Departures

While all eyes were on Albany in October 2014 for the centenary of the Australian troop departure, there were some smaller scale commemorative events in Perth to recognise an oft-forgotten element: the fact that almost all Western Australian troops departed from the Blackboy Hill Training Camp and on through the port of Fremantle.

These troops, most of them with the 11th and 12th Battalions, marched out of Blackboy Hill on October 31 1914, and made their way down to Fremantle by train. There, they boarded the ships Ascanius and Medic, and these did not go down to Albany to meet the rest of the fleet that had gathered there- rather, after pulling up anchor from on October 31st, they waited off the coast until the rest of the convoy caught up with them on November 2nd.

Far too often, it is either stated or assumed that all troops left through Albany. The great irony is, even Albany soldiers travelled up to Perth for training before departing from Fremantle.

The City of Fremantle (and other partners) acknowledged this fact with a series of events over October 30th and 31st, beginning at Blackboy Hill and ending in Fremantle. I attended the Blackboy Hill events, but as I was on my way to the Albany events the next day, I'll turn the reporting over to a friend who attended the Fremantle side of things.

Blackboy Hill- 30th October 2014

The evening at Blackboy Hill was a great family event, featuring many groups who are working on Western Australia's military history. From the 10th Light Horse to historians and archaeologists from Notre Dame University, from re-enactors to pipe bands, from antique vehicles to the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre group writing the Blackboy Hill is Calling history, there were presentations, demonstrations and displays of interest to all.

Fremantle- 31st October 2014

While I was busy driving down to Albany the next day to join the events there, the commemoration of Western Australia's troops continued in the harbour town of Fremantle. The following photographs and experiences come courtesy of a friend, Michael Gregg, who was there to see the troop march arrive.

Following the same general route as the troops did in 1914, a representative group made their way from Blackboy Hill down to Fremantle via railway, with the Hotham Valley steam train fitted out to match the original.

Michael was waiting at Fremantle harbour to watch them arrive, and gives a very evocative description of his experience.

#

It’s the drums that hit me.

A minute ago, I was a rowdy bystander at yet another street parade, a festive spectator gawking and bored, waiting for the action to start.

And it does. A quiet paradiddle on the snare drum, and suddenly we are in a different world.

The skirl of the bagpipes cuts in, slashing across the present like a knife. In front of me a horse kicks reflexively, and the khaki rider steps her forward, leading the column where?

Flags lift and droop, and behind them, boots lift and step. Khaki uniforms pass me, stepping in time, slouch hats hiding in shadow the identity of the wearer. No matter – I know you, the hope and glory of our young nation, striding into the world.

Past the Customs House, the column curls, stepping out now onto alien territory, a first no-mans land, a place of embarkation and separation. The flag waving spectators run to catch up, to be part of the transition and the tradition. A curt official orders me away. “You can’t come in here”. It blurs past me, but how cutting to the loved one whose very heart is stumbling up a flimsy gangway, burdened by a bulging pack of official requirements and a desperate sense of separation.

Quietly we gather together. Flashes flash, and cameras film. Voices speak, extolling great glories. But one quiet voice cuts through - a reflection of one man’s life, legacy and suffering. Lest we forget what war meant to the very real participants. We hang in silence, caught in a moment of awareness. And then the impossibly polished bugle sounds. It is The Last Post. We stand, remember and respect. And then the “Rouse” lifts us, jolts us put of our reverie. The jaunty scale tells us we are alive, and grateful to be so. Politicians ease off for their scheduled “photo ops”, but the crowd remain, standing, remembering, marvelling.

Eventually I stop crying.

#

Some of Michael's photographs from the event are below.

A big thank you to Michael for sharing his experience and photographs.

Next up: Anzac Albany.

These troops, most of them with the 11th and 12th Battalions, marched out of Blackboy Hill on October 31 1914, and made their way down to Fremantle by train. There, they boarded the ships Ascanius and Medic, and these did not go down to Albany to meet the rest of the fleet that had gathered there- rather, after pulling up anchor from on October 31st, they waited off the coast until the rest of the convoy caught up with them on November 2nd.

Far too often, it is either stated or assumed that all troops left through Albany. The great irony is, even Albany soldiers travelled up to Perth for training before departing from Fremantle.

The City of Fremantle (and other partners) acknowledged this fact with a series of events over October 30th and 31st, beginning at Blackboy Hill and ending in Fremantle. I attended the Blackboy Hill events, but as I was on my way to the Albany events the next day, I'll turn the reporting over to a friend who attended the Fremantle side of things.

Blackboy Hill- 30th October 2014

The evening at Blackboy Hill was a great family event, featuring many groups who are working on Western Australia's military history. From the 10th Light Horse to historians and archaeologists from Notre Dame University, from re-enactors to pipe bands, from antique vehicles to the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre group writing the Blackboy Hill is Calling history, there were presentations, demonstrations and displays of interest to all.

10th Light Horse display

Era-appropriate tents set up for the kids who were camping overnight

Military vehicle display

A/Prof Deborah Gare and Dr. Shane Burke of Notre Dame discuss their work

The student pipe band did a fabulous job

Representing the original enlistees who marched away from the camp

Fremantle- 31st October 2014

While I was busy driving down to Albany the next day to join the events there, the commemoration of Western Australia's troops continued in the harbour town of Fremantle. The following photographs and experiences come courtesy of a friend, Michael Gregg, who was there to see the troop march arrive.

Following the same general route as the troops did in 1914, a representative group made their way from Blackboy Hill down to Fremantle via railway, with the Hotham Valley steam train fitted out to match the original.

Michael was waiting at Fremantle harbour to watch them arrive, and gives a very evocative description of his experience.

#

It’s the drums that hit me.

A minute ago, I was a rowdy bystander at yet another street parade, a festive spectator gawking and bored, waiting for the action to start.

And it does. A quiet paradiddle on the snare drum, and suddenly we are in a different world.

The skirl of the bagpipes cuts in, slashing across the present like a knife. In front of me a horse kicks reflexively, and the khaki rider steps her forward, leading the column where?

Flags lift and droop, and behind them, boots lift and step. Khaki uniforms pass me, stepping in time, slouch hats hiding in shadow the identity of the wearer. No matter – I know you, the hope and glory of our young nation, striding into the world.

Past the Customs House, the column curls, stepping out now onto alien territory, a first no-mans land, a place of embarkation and separation. The flag waving spectators run to catch up, to be part of the transition and the tradition. A curt official orders me away. “You can’t come in here”. It blurs past me, but how cutting to the loved one whose very heart is stumbling up a flimsy gangway, burdened by a bulging pack of official requirements and a desperate sense of separation.

Quietly we gather together. Flashes flash, and cameras film. Voices speak, extolling great glories. But one quiet voice cuts through - a reflection of one man’s life, legacy and suffering. Lest we forget what war meant to the very real participants. We hang in silence, caught in a moment of awareness. And then the impossibly polished bugle sounds. It is The Last Post. We stand, remember and respect. And then the “Rouse” lifts us, jolts us put of our reverie. The jaunty scale tells us we are alive, and grateful to be so. Politicians ease off for their scheduled “photo ops”, but the crowd remain, standing, remembering, marvelling.

Eventually I stop crying.

#

Some of Michael's photographs from the event are below.

The train coming in

Arriving at the station with the band all ready to greet it. The next few photographs show parts of the march to the docks, with various units represented.

And below is the end point at the Maritime Museum on Victoria Quay, just beside the spot where the ships were tied up back in 1914.

A big thank you to Michael for sharing his experience and photographs.

Next up: Anzac Albany.

Tuesday, July 14, 2015

Arthur Tyrrell Williams and The Gallant Light Horse

Several Olive Street soldiers returned from the war and became closely involved in the work of the RSSILA (Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' Imperial League of Australia, later to become the RSL (Returned and Services League)).

They were strong advocates for their fellow returned servicemen, and one of the most passionate was Arthur Tyrrell Williams, who lived at 139 Barker Road on the corner of Olive Street in Subiaco. Before, during and after the war, he was quite a remarkable man in many different ways.

Before the war, Dublin-born Williams had been a civil servant working in the Lands Department. In 1908, he married Nellie Lalage Stacy, and in 1910, he became a land agent in partnership with his father-in-law, George Stacy. Over the next thirty years, Williams would involve himself in any number of land and mining ventures around Western Australia, always ambitious, though not always successful.

Nellie Williams was an interesting individual in her own right; before marriage, she was a piano teacher, and at 18 had become the youngest musician in the Commonwealth to obtain the L.A.B degree in Music (Licentiate of the Associated Board of the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, London, in conjunction with the University of Adelaide).

But within a few weeks, greater physical problems began to emerge. In the end, although he had managed to keep fighting after the initial injury, Williams had to be removed to Malta for further treatment, and from there to Italy.

Over the course of several months, his long list of maladies would grow to include dental caries and pyorrhoea (inflammation of the gums), ptomaine poisoning (food poisoning), plus sciatica, lumbago, rheumatism, myalgia, and fibrositis (fibromyalgia). Williams believed that the concussion of the bomb blasts was responsible for his aches and pains; another contributing factor was a fall from scaffolding whilst supervising building works in Malta.

In 1918, he was embroiled in controversy after signing himself as the state secretary for the Western Australian branch of the Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' League, implying that this organisation was the official Western Australian branch of the national RSSILA (later to become the RSL). At the time, the A.I.F. Returned Soldiers' and Sailors' Association (the RSA) was also active in Western Australia, and the general secretary of that group, Charles Taylor, objected strenuously to Williams claiming to represent the state to the nation.

Deep divisions existed between the groups, and there was much shifting, changing and blending between they and the RSSILA over time, but from 1919, Williams appears to have bowed out of the ongoing power struggles amongst those at the highest levels of action.

They were strong advocates for their fellow returned servicemen, and one of the most passionate was Arthur Tyrrell Williams, who lived at 139 Barker Road on the corner of Olive Street in Subiaco. Before, during and after the war, he was quite a remarkable man in many different ways.

Before the war, Dublin-born Williams had been a civil servant working in the Lands Department. In 1908, he married Nellie Lalage Stacy, and in 1910, he became a land agent in partnership with his father-in-law, George Stacy. Over the next thirty years, Williams would involve himself in any number of land and mining ventures around Western Australia, always ambitious, though not always successful.

Nellie Williams was an interesting individual in her own right; before marriage, she was a piano teacher, and at 18 had become the youngest musician in the Commonwealth to obtain the L.A.B degree in Music (Licentiate of the Associated Board of the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, London, in conjunction with the University of Adelaide).

Nellie Lalage Stacy

Arthur Tyrrell Williams at war

Williams was 38 years of age when the Great War began in 1914, and he had a long military history of his own, having served during the Rhodesian Rebellion in 1896-97, and in the Boer War between 1899- 1902 as a Lieutenant Senior Cadet. He was amongst the first to enlist in August 1914, and with his prior experience, he applied for a commission in the 10th Light Horse Regiment. He was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant, and sailed for Gallipoli.

Williams was 38 years of age when the Great War began in 1914, and he had a long military history of his own, having served during the Rhodesian Rebellion in 1896-97, and in the Boer War between 1899- 1902 as a Lieutenant Senior Cadet. He was amongst the first to enlist in August 1914, and with his prior experience, he applied for a commission in the 10th Light Horse Regiment. He was appointed a 2nd Lieutenant, and sailed for Gallipoli.

Writing home on 31 May 1915, Williams recounted a lucky escape from death that would, though he didn't yet realise it, change the course of his war experience:

Am still safe and sound although slightly wounded. At a point in our line of fire trenches, only eight or nine yards from the enemy, I was on duty in command of supports to a sortie made by 60 of our regiment. This party was led by two of our lieutenants, and whilst busy filling up the fire-trench two bombs fell into our supports trench. I saw them fizzling about two paces behind me, and I knew I was too late to pitch them back again or 'duck' for cover; so I just turned my face away and waited.The same letter, published to The West Australian in July of that year, also provides colourful detail of the dangers of bathing at Gallipoli, and is well worth a read at the link above. He ends by stating, "I have quite recovered now and feel no ill effects from my slight injury."

Both went off, and at each bang I felt a corresponding bang on my back, but after the dust, smoke, and fumes had cleared away (not being conscious of anything more than a bruised feeling in my back) I carried on with my work, which was so lively and absorbing that I had no time to think of anything else.

In a lull in the awful inferno of the at tack I felt a sensation of wetness on my back. I reported to the nearest dressing station and had a field dressing put on four punctures from fragments. Afterwards I walked down to the beach and had the pieces picked out and am now as well as ever. On making an examination of my equipment, I find that all the large pieces of bomb which came my way struck my revolver belt, haversack, and great coat. My emergency ration tin has a good sized hole in it. I was very lucky to get off so lightly considering that nearly all the men hit by bombs are terribly mutilated.

But within a few weeks, greater physical problems began to emerge. In the end, although he had managed to keep fighting after the initial injury, Williams had to be removed to Malta for further treatment, and from there to Italy.

Over the course of several months, his long list of maladies would grow to include dental caries and pyorrhoea (inflammation of the gums), ptomaine poisoning (food poisoning), plus sciatica, lumbago, rheumatism, myalgia, and fibrositis (fibromyalgia). Williams believed that the concussion of the bomb blasts was responsible for his aches and pains; another contributing factor was a fall from scaffolding whilst supervising building works in Malta.

Williams describes his illnesses and injuries

(Source: NAA)

While at Gallipoli, he also collected seeds from the Gallipoli rock-rose (Cistus canastens). He sent these home to his father-in-law George, who became one of the first to propagate the plants in Australia.

After several months moving through the hospital system into Egypt and England, it was clear he would not return to fighting fitness, and he was sent back to Australia for change. For someone so passionately committed to the war effort, this was not a happy circumstance, and he was determined to get back to the fight. He did manage to return Egypt by mid-1916. But he fared no better the second time around, adding neuritis and neurasthenia to his list of ills, suggesting that there may have been an ongoing psychological element to his trouble.

He returned to Australia again in 1917, and was permanently back on home soil from that point forward.

Recruitment

An ANZAC wildflower, propagated by George Stacy from seeds sent home by A. T. Williams

(Source: Western Mail)

After several months moving through the hospital system into Egypt and England, it was clear he would not return to fighting fitness, and he was sent back to Australia for change. For someone so passionately committed to the war effort, this was not a happy circumstance, and he was determined to get back to the fight. He did manage to return Egypt by mid-1916. But he fared no better the second time around, adding neuritis and neurasthenia to his list of ills, suggesting that there may have been an ongoing psychological element to his trouble.

He returned to Australia again in 1917, and was permanently back on home soil from that point forward.

Recruitment

Lacking the ability to fight, Williams instead worked as an instructor at the Blackboy Hill camp, and became an active recruiter. He spoke at public gatherings, wrote impassioned letters, and sent poetry to the newspapers.

He was not the only family member appealing to the public through verse. Father-in-law George Stacy, who was a former journalist and was involved in theatre productions locally, was a supporter of the "Yes" vote in the divisive conscription referenda. He was as prone to dramatic expression as his son-in-law, and after W. R. Winspear's famous work The Blood Verse circulated as an anti-conscription message, Stacy responded in kind.

Arthur Tyrrell Williams took his recruitment approach a step further again. With pianist wife Nellie, he composed a piece of music titled The Gallant Light Horse, aimed at encouraging others to join the fight.

Hark to the cry from the trenches,

Think of our men over

there!

Hardship or war never quenches

Their dash and courage

to dare.

What are we? Neutrals or aliens?

Hearing their cry, and afraid —

"Send reinforcements,

Australians,

Send out another brigade.

Reg'ments that won fame

and glory,

Reg'ments that never will die,

Living in legend and

story,

Crooned in the child's lullaby.

Glory and fame must

not perish,

Famous battalions must live.

Shades of dead

heroes we cherish,

Call to Australia to give.

Australia, gem

of the ocean,

Home of the brave and the free,

Name that

inspires emotion —

Synonym of liberty.

List, Parliamentary

benches,

Will you her fair name besmirch?

Hark to the cry

from the trenches,

Don't leave us here in the lurch."

From The Daily News, 22 February 1917

"Why is your face so white, mother? Why do you choke for

breath?"

"Oh, I have dreamt in the night, my son,

That I doomed a man to death."

"I dreamt, my son, that I left a man

To perish for want of aid,

Though he fought to guard your mother, my son,

For of death he was not afraid.

"He had sweated and bled and starved for us,

Who were nothing of kin to him;

But he fought and wrought till his muscle sagged

And his once clear eye grew dim.

"And though he hoarsely called, "Send help!"

No heed I took of his cry;

When 'Yes' would have saved him I answered 'No,'

And I left him there to die.

"As I saw him sink, by numbers slain,

I woke with a frightened scream.

Oh! God, be thanked for His mercy great,

What I saw was only a dream.

"O, little son! O my son!

That dream was a message sent:

To guide my feet in the path aright,

That vision was surely meant.

"To-day I will answer that dream-man's call,

And thousands will LIVE to bless

Her who for country and country's sons

Had courage to answer 'Yes!''

"Oh, I have dreamt in the night, my son,

That I doomed a man to death."

"I dreamt, my son, that I left a man

To perish for want of aid,

Though he fought to guard your mother, my son,

For of death he was not afraid.

"He had sweated and bled and starved for us,

Who were nothing of kin to him;

But he fought and wrought till his muscle sagged

And his once clear eye grew dim.

"And though he hoarsely called, "Send help!"

No heed I took of his cry;

When 'Yes' would have saved him I answered 'No,'

And I left him there to die.

"As I saw him sink, by numbers slain,

I woke with a frightened scream.

Oh! God, be thanked for His mercy great,

What I saw was only a dream.

"O, little son! O my son!

That dream was a message sent:

To guide my feet in the path aright,

That vision was surely meant.

"To-day I will answer that dream-man's call,

And thousands will LIVE to bless

Her who for country and country's sons

Had courage to answer 'Yes!''

A VISION- AND AND ANSWER

GEORGE STACY, St. George's Terrace, Perth. Without apology to

W. R. Winspear, Sydney.

The Daily News, 27 October 1916

W. R. Winspear's original The Blood Vote

(Source: Museum Victoria)

Arthur Tyrrell Williams took his recruitment approach a step further again. With pianist wife Nellie, he composed a piece of music titled The Gallant Light Horse, aimed at encouraging others to join the fight.

The sheet music is held by the State Library of Western Australia, and when I first came across it, I put out a call to see if anyone would be able to assist by recording it. The request was answered by the wonderful Tim Chapman, Director of Music at Perth's St Hilda's Anglican School for Girls, who was not only able to play the piano but also provided the vocals.

Unheard for many decades, I'm now able to present to you The Gallant Light Horse, by Lt Arthur Tyrrell Williams and Nellie Lalage Williams, very much as it would have sounded in 1917.

Unheard for many decades, I'm now able to present to you The Gallant Light Horse, by Lt Arthur Tyrrell Williams and Nellie Lalage Williams, very much as it would have sounded in 1917.

Advocacy, Innovation, and the RSSILA debate

Williams did not only encourage others to go to war without a thought for what they would face. He was also and early and active advocate for Western Australia's returned soldiers.

In 1917, guided by his extensive experience in the Lands Department, he proposed a new repatriation settlement in the Riverton area. The idea was somewhat controversial, as the sandy conditions were ill-suited to the planned purpose of group farming. After much negative publicity, the project did not end up going ahead, and Williams himself quietly gave up his allotment of land in 1921.

In vocal letters to the newspaper written by himself and his opponents, Williams often gave the impression of a man of strong opinions and ambition, and it is plain that he was not always popular.

Williams did not only encourage others to go to war without a thought for what they would face. He was also and early and active advocate for Western Australia's returned soldiers.

In 1917, guided by his extensive experience in the Lands Department, he proposed a new repatriation settlement in the Riverton area. The idea was somewhat controversial, as the sandy conditions were ill-suited to the planned purpose of group farming. After much negative publicity, the project did not end up going ahead, and Williams himself quietly gave up his allotment of land in 1921.

In vocal letters to the newspaper written by himself and his opponents, Williams often gave the impression of a man of strong opinions and ambition, and it is plain that he was not always popular.

A public joke at Williams' expense in 1919

(Source: The Sunday Times)

In 1918, he was embroiled in controversy after signing himself as the state secretary for the Western Australian branch of the Returned Sailors' and Soldiers' League, implying that this organisation was the official Western Australian branch of the national RSSILA (later to become the RSL). At the time, the A.I.F. Returned Soldiers' and Sailors' Association (the RSA) was also active in Western Australia, and the general secretary of that group, Charles Taylor, objected strenuously to Williams claiming to represent the state to the nation.

Deep divisions existed between the groups, and there was much shifting, changing and blending between they and the RSSILA over time, but from 1919, Williams appears to have bowed out of the ongoing power struggles amongst those at the highest levels of action.

He did, however, continue his fight to improve conditions, particularly for those who had been wounded in battle and were unable to return to their former occupations. Undaunted by the failure of his Riverton scheme and the bitter politics of the returned soldiers' world, he launched a new venture in which wounded veterans would make and deliver sandwiches to businesses in the Perth Central Business District.

Although the Returned Soldiers' Sandwich Supply was operated by others through the 1920s, such as the unfortunate Fred Johnson, Williams was still described as a caterer in electoral rolls through to the 1930s, later describing himself as a mining investor. After that point, his public life became a lot quieter, with mentions only of various mining ventures appearing in the newspapers, and the publication of a handful of plays.

But war was not done with the Williams family yet. On 18 September 1943, The Daily News published an article about the Williams' son Jack, who was an air observer with the RAAF in England, training to become a night fighter.

The former Hale School boy and gold assayer, who had been just three years of age when his father first went to war, had survived a close shave in the air when his out-of-control plane pulled out of a dive with only 150 feet to spare. The article also mentioned that he had married an English girl, Hazel, two weeks previously.

The very day after the article appeared, Jack was killed in a flying accident.

Arthur himself died in 1951, aged 75. He may have faded from public view over the years, but when it counted most immediately after the war, he was an influential figure in the lives of returned servicemen in Perth.

The workers of the Returned Soldiers' Sandwich Supply in 1919

(Source: Western Mail)

Although the Returned Soldiers' Sandwich Supply was operated by others through the 1920s, such as the unfortunate Fred Johnson, Williams was still described as a caterer in electoral rolls through to the 1930s, later describing himself as a mining investor. After that point, his public life became a lot quieter, with mentions only of various mining ventures appearing in the newspapers, and the publication of a handful of plays.

But war was not done with the Williams family yet. On 18 September 1943, The Daily News published an article about the Williams' son Jack, who was an air observer with the RAAF in England, training to become a night fighter.

The former Hale School boy and gold assayer, who had been just three years of age when his father first went to war, had survived a close shave in the air when his out-of-control plane pulled out of a dive with only 150 feet to spare. The article also mentioned that he had married an English girl, Hazel, two weeks previously.

The very day after the article appeared, Jack was killed in a flying accident.

Arthur himself died in 1951, aged 75. He may have faded from public view over the years, but when it counted most immediately after the war, he was an influential figure in the lives of returned servicemen in Perth.

Friday, April 24, 2015

Olive Street in the News

Since releasing the Olive Street results, the project has been travelling far and wide! Here are some of the places it will appear- to be updated with links as each is complete.

City of Subiaco- Subiaco Museum exhibit, When the Great War Came to Subiaco

The City of Subiaco has an exhibit running at the moment, featuring great work by museum coordinator Erica Boyne, Gallipoli Dead from Western Australia coordinator Shannon Lovelady, and many others. It also features a large panel that details some of the early work on the Olive Street story, and the exhibit gives great additional context to the research.

Well worth a visit, and free. See here for more details, including opening hours.

City of Subiaco- Lunchtime Talk in the Library

I went along to the Subiaco Library on Friday 17th April to talk about the Olive Street research, and we had around 50 people in attendance. A very nice afternoon, and good to see many community members interested in the project. We'll be aiming to do more of these at different times in coming months.

Interview with Nathan, Nat and Shaun on Nova 937- April 24th

Leading into the centenary of the ANZAC landings on April 25th, I chatted to breakfast radio crew Nathan, Nat and Shaun on Nova 937. They are an absolute delight to speak with, and it was a much appreciated opportunity to tell the wider world about the Landscape of Loss project and the Olive Street outcomes. Below, the two interview segments are embedded, with kind permission of Nova.

Part 1:

Part 2:

Coverage in The West Australian, Saturday 25th April 2015

Journalist Katherine Fleming wrote a beautiful piece about Olive Street for The West Australian's ANZAC Day Centenary issue, which also resulted in me getting to meet Murray Kerrigan, the grandson of Olive Street soldier (and Military Medal nominee) Tom Kerrigan. Both the online and print editions go into a great level of detail, including a graphic that shows the toll suffered by Olive Street residents. Having the added information about Tom Kerrigan's life from his direct descendants is a great addition to the overall Olive Street story, and I really appreciate Katherine's fantastic work in bringing it all together.

Check out the full story here.

State Records Office Family History Discovery Day

On Sunday 26th April, I'm one of several local historians presenting our work at the State Records Office First World War Family History Discovery Day in Perth's Cultural Centre. We'll be at the State Theatre complex from 10am to 4pm, and I'm speaking at 2pm about the Landscape of Loss, and how you can find your own family's place in it.

More information here.

Blackboy Hill is Calling

On May 3rd at 3pm, the social history of the Blackboy Hill training camp, titled Blackboy Hill is Calling, will be launched by the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre group up at Greenmount. I've contributed a chapter on brothers who trained at Blackboy Hill.

There's also an earlier launch and a talk at the State Library on Monday 27th April at 11am.

See the details of both here.

City of Subiaco- Subiaco Museum exhibit, When the Great War Came to Subiaco

The City of Subiaco has an exhibit running at the moment, featuring great work by museum coordinator Erica Boyne, Gallipoli Dead from Western Australia coordinator Shannon Lovelady, and many others. It also features a large panel that details some of the early work on the Olive Street story, and the exhibit gives great additional context to the research.

Well worth a visit, and free. See here for more details, including opening hours.

City of Subiaco- Lunchtime Talk in the Library

I went along to the Subiaco Library on Friday 17th April to talk about the Olive Street research, and we had around 50 people in attendance. A very nice afternoon, and good to see many community members interested in the project. We'll be aiming to do more of these at different times in coming months.

Interview with Nathan, Nat and Shaun on Nova 937- April 24th

Leading into the centenary of the ANZAC landings on April 25th, I chatted to breakfast radio crew Nathan, Nat and Shaun on Nova 937. They are an absolute delight to speak with, and it was a much appreciated opportunity to tell the wider world about the Landscape of Loss project and the Olive Street outcomes. Below, the two interview segments are embedded, with kind permission of Nova.

Part 1:

Part 2:

Coverage in The West Australian, Saturday 25th April 2015

Journalist Katherine Fleming wrote a beautiful piece about Olive Street for The West Australian's ANZAC Day Centenary issue, which also resulted in me getting to meet Murray Kerrigan, the grandson of Olive Street soldier (and Military Medal nominee) Tom Kerrigan. Both the online and print editions go into a great level of detail, including a graphic that shows the toll suffered by Olive Street residents. Having the added information about Tom Kerrigan's life from his direct descendants is a great addition to the overall Olive Street story, and I really appreciate Katherine's fantastic work in bringing it all together.

Check out the full story here.

State Records Office Family History Discovery Day

On Sunday 26th April, I'm one of several local historians presenting our work at the State Records Office First World War Family History Discovery Day in Perth's Cultural Centre. We'll be at the State Theatre complex from 10am to 4pm, and I'm speaking at 2pm about the Landscape of Loss, and how you can find your own family's place in it.

More information here.

Blackboy Hill is Calling

On May 3rd at 3pm, the social history of the Blackboy Hill training camp, titled Blackboy Hill is Calling, will be launched by the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre group up at Greenmount. I've contributed a chapter on brothers who trained at Blackboy Hill.

There's also an earlier launch and a talk at the State Library on Monday 27th April at 11am.

See the details of both here.

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

Landscape of Loss: Olive Street Stories

This is the third of three posts about Olive Street in Subiaco, Western Australia. The introduction can be found here, some statistics and examples here, and a map here.

#

Throughout the fifty houses on Olive Street, there were an untold number of stories about how the war was felt in Subiaco. For every person who went to war, there were several left at home to wait, worry, and mourn if they did not return. For every person who came home, there was a lifetime of reckoning their First World War experience, and some found it considerably harder than others to get back to life as they had known it.

Picture the entire street from the records available, and you will see neighbours of every variety. Professional and working class, Church of England and Roman Catholic, born overseas or interstate or locally, and working all across Western Australia in a range of jobs. Some were married with families, and some still lived with their parents. There were larger than life characters scattered up and down Olive Street, and the war affected them in many different ways.

Fathers and Sons: The Durkin Family of 22 Olive Street

Nicholas Durkin was one of the tallest men to enlist from Olive Street, standing over 6’ in height. He was a prospector and miner who worked in some of Western Australia’s most remote outposts, and he was accordingly as rough and ready as you might expect.

In the earlier years of the 20th century, wife Mary Ann had raised their six children, including sons Vincent and Bernard, in the Goldfields centre of Kalgoorlie. During the same time, Nicholas had worked in places as remote as Roebourne and Carnarvon, and his behaviour raised the occasional eyebrow.

In 1910, after the success of a prospecting venture at Bullfinch, Nicholas commenced a six-week celebration comprising “one continual drinking bout”. During this time, Nicholas declared to many fellow guests at the Oddfellows’ Hotel in Fremantle that he and the married proprietor Mrs. Purcell had spent some time in the bedroom together. Mrs. Purcell denied this, and with many witnesses on her side, Nicholas was charged with defamation, and was convicted. The details of the case were widely reported in newspapers around the state.

Mary Ann remained loyal, and the family moved away from the Goldfields and into Olive Street in 1914. When war was declared, Vincent was the first to enlist in 1915, followed shortly after by Bernard. Never one to shy away from adventure, Nicholas wasn’t going to be left behind- he reduced his age by ten years, from 52 to 42, and put his own name down as well.

After many charges of being Absent Without Leave before even departing Australian shores, it must have been clear that military discipline and Nicholas Durkin were not an ideal combination. But it was on arrival in England that Nicholas wasn’t able to complete the basic drills and marches due to his age, and at that, he was discovered, sent home, and discharged. Vincent and Bernard fought out the remainder of the war, and returned home in 1919.

Nicholas died in 1930, aged 67. Bernard married and had a child, but was only 54 when he passed away in 1942. Vincent would later go on to serve in the Second World War, and acted as Secretary of the North-East Fremantle Sub-Branch of the RSL. He is pictured on the left at the 1920 wedding of his sister Fayne (far right), with his future wife Florence Hollins standing behind him.

The family’s relationship with housemate George Hunter is unclear. He was a contractor working on a farm in the country town of Wagin, and his wife Ada Allison Myrtle Hunter gave 22 Olive Street as her next of kin address when George enlisted, one day after Vincent Durkin. George was injured a number of times, including one occasion where he slipped off a duckboard and landed on a concealed, upright bayonet, which pierced his foot. Like the other residents of number 22, he survived the fighting and returned home in 1919.

Brothers in Arms: The Rogers Family of 23 Olive Street

Directly across the road from the Durkin home, at 23 Olive Street, the four soldier sons of George and Annie Rogers all enlisted between November 1915 and April 1916. In short order, they were off to the Western Front, ready to do their bit for the war effort. The oldest, miner George, was 24- the youngest, labourer William, only 18.

After enlisting, George married Stella Adella North. Their son, also named George, would be born in his father’s absence- and they would never get to meet. George was killed in action at Passchendaele in 1917, leaving Stella a widow at just 21 years of age.

David Rogers also died a few months later, killed during fierce fighting at Dernancourt. Witnesses said he had gone to the aid of a fallen soldier, only to be struck by a bullet, grenade or shell in the stomach. He was seriously wounded and would not allow anyone to touch him, so had to be left where he was in a position where the German Army would shortly overtake the ground. Many assumed he must have become a prisoner of war, but there was no record of that- he was eventually listed as killed in action after an inquiry.

James Rogers returned home early with gunshot injuries to his hand, while William was also shot in the hand and head, but fought on to the end of the war.

There were many sets of Olive Street brothers who enlisted and fought together, including the three Rankin brothers who lived at 27 Olive Street, a couple of houses up from the Rogers family. Most lost at least one sibling to the fighting.

Luck and Lack Thereof

Wally D'raine was a well-known character around Perth, having been born in the north of England and having come to Western Australia via the United States. He was a successful butcher with several stores, and he approached his work with a salesman's enthusiasm and flair. No publicity was bad publicity for D'raine, who fell out with both his brother and his wife in very public ways.

He was living at 74 Olive Street in 1915 when he enlisted for war, initially becoming a sergeant in the 10th Light Horse Regiment.

Wally also had a combination of luck that was at once terrible and fortunate. He was being treated for bronchitis at the 53rd Casualty Clearing Station near Bailleul in 1917 when an enemy plane dropped a bomb, resulting in serious injuries from shrapnel. After six months of treatment for wounds to his shoulder, chest, face and leg, he was invalided back to Australia and took no further part in the war.

A similar piece of terrible luck befell Ernest Lyndon Menagh, whose brother John Wilson Menagh had lived at 31 Olive Street. A corporal with the 4th Divisional Ammunition Column, he was billeted in a three-storey house near Peronne, and was asleep when an air raid scored a direct hit. He received serious wounds to the legs and abdomen, and died three days later at the 35th Casualty Clearing Station.

Above and Beyond the Call

Three residents of Olive Street were recommended for or awarded medals for bravery during the First World War.

KERRIGAN, Thomas Michael (74 Olive Street)- Military Medal

The Kerrigan family were well-known in the Kulin area, where father John was a local publican. After their son Tom enlisted in 1915, they moved into Olive Street for the remainder of the war years.

At the infamous battle of Pozieres in July 1916, where numerous other Olive Street soldiers were wounded or killed, Tom’s efforts under fire earned him a recommendation for the Military Medal.

GWYTHER, Edward McKinnon (87 Olive Street)- Distinguished Conduct Medal and Military Medal

Edward McKinnon Gwyther was a 19-year-old clerk who had lived in Olive Street and worked in Kalgoorlie, and he was amongst the first to enlist in August 1914. After several bouts of serious illness during the fighting at Gallipoli, he rose through the ranks to become a sergeant. He was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry and devotion to duty at Jeancourt in September 1918, and also recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

HENDERSON, William John (86 Bagot Road)- Distinguished Conduct Medal

William Henderson was an accountant and legal manager who lived at 86 Bagot Road, on the corner of Olive Street, with his wife Annie. His brother George, a 21-year-old labourer, gave the same address when he enlisted in 1914, and also listed William as his next of kin.

William was an experienced soldier, having previously fought in the Boer War for two years, and his application for a commission with the 10th Light Horse Regiment in 1914 saw him given the rank of Sergeant. He fought at Gallipoli, where in August at the infamous battle of Hill 60, his extraordinary efforts would see him Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

The story of Henderson's 37-hour hand-to-hand fight to hold a trench is inspiring enough, but his service record reveals that his actions required double the effort. From the moment he arrived in Egypt, he was suffering a recurrence of long-term health problems with his digestive system that saw him taken out of the line multiple times. He had only been back in the line for a brief time from his latest illness when called on to fight at Hill 60. No longer able to digest the field diet, he returned to Australia for change in 1917. But unwilling to remain at home, he went back to Egypt at the end of that year. He saw no further fighting, and returned to Australia again within the month.

William was an active advocate for returned soldiers, and after moving back to his home state of Victoria, became the General/ Federal Secretary of the RSSILA (Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia, later to become the RSL). In 1921, after years of battling the same problems, he was finally too tired to fight on. He died in the No 11 Australian General Hospital in Melbourne in March that year, with his cause of death given as intestinal obstruction and exhaustion.

His brother George, also resident at 86 Bagot Road, was killed in action at Messines in 1917.

A World of Grief at Number 90: the McKinnons and the Sampfords

Though many houses in Olive Street suffered losses, the home at number 90 received a much larger share of bad news than most.

Two different families were associated with the house throughout the war years- first, the McKinnons from 1915- 1916, and then the Sampfords from 1917- 1918.

Annie Catherine “Kit” Fitzgerald married husband David McKinnon, a well-known soccer player for the Caledonian team, after he enlisted in 1915. By the time he departed for war with his brother Daniel, she was expecting their first child.

Tragedy struck early at number 90. Baby David Joseph McKinnon was born in January 1916, and died within a few days. Kit was left to mourn the loss of her baby alone, and her grief would expand in July that year, when David was killed in action at Pozieres. His brother Daniel died one day later in a German Prisoner of War camp of wounds received at Fromelles. The following year, Kit’s closest brother Frank Fitzgerald was also killed in action. On the second anniversary of her husband's death, Kit (by then living around the corner at 82 Bagot Road) placed a newspaper notice mourning all three.

She never remarried, and upon her death in 1962, she was reunited

with her son, buried in the same grave at Karrakatta cemetery.

Like the Durkin family at the other end of Olive Street, the Sampfords had a lot of character. Ernest Sampford was a father of seven children between the ages of 9 and 27, and he enlisted with three of his sons to fight.

Arthur was the first son to enlist at the outbreak of war in 1914, and he landed at Gallipoli with the rest of the 11th Battalion. He was seriously wounded within days, with a gunshot wound to the face and an un-united compound fracture of his arm resulting in his return home.

Not long before Arthur arrived back on Australian shores, 21-year-old Charles and 23-year-old Billy enlisted on the same day in July 1915. They fought with the 48th Battalion at Pozieres, where Billy was killed in action. Charles survived the fight, but ran into trouble not long after. While on active duty, he left his post contrary to orders, and at his subsequent court martial was sentenced to ten years of penal servitude. This was commuted to two years of imprisonment with hard labour, but after a year in prison, Charles was released early and returned to the Front. Within weeks, he too was killed in action at Jeancourt.

44-year-old carpenter Ernest was the last to enlist in November 1915, following his sons across to the Western Front. He spent just six days in the field before being urgently removed to hospital with bronchitis and pleurisy. With old age listed as the reason, he was discharged from the AIF and returned to Australia. He later returned to London as a munitions worker for a brief period, before coming back to Australia. He died at the Edward Millen Home in Victoria Park in 1925.

On the Home Front

From 139 Barker Road, enthusiastic volunteer Arthur Tyrrell Williams went to Gallipoli with the 10th Light Horse Regiment. But in 1915, he was wounded in action and forced to return to Australia. On the home front, he became a fervent campaigner for recruitment in Western Australia, speaking at rallies and even writing a patriotic song, The Gallant Light Horse, with his pianist wife Nellie.

Arthur was not just a man of words. He was also prominent in working to assist returned servicemen, becoming Western Australia’s secretary of the RSSILA (RSL), and proposing a settlement scheme for the Riverton area. When that failed, he commenced a business in which wounded soldiers made and distributed sandwiches to offices in central Perth.

Beyond the War

Many Olive Street soldiers had a difficult time after their return from war. Some were arrested for public drunkenness, abusive language, and running betting operations. Others were divorced or separated, or charged with the maintenance of illegitimate children. Many of those who made it home died far too young, within a decade of their return.

Amidst the difficulties, there was also hope. Widows like Stella Rogers remarried and began new families. New careers began for many whose physical capacity had been altered by their war experiences, and some achieved great success.

The Landscape of Loss study seeks to examine the long-term social change that resulted from the First World War, and over time will bring together as many stories as possible of life after the war. Most of those who had been resident in Olive Street during the war years had moved elsewhere by 1920, but during those years, the residents had suffered together and pulled through. For many, their challenges were just beginning.

#

Throughout the fifty houses on Olive Street, there were an untold number of stories about how the war was felt in Subiaco. For every person who went to war, there were several left at home to wait, worry, and mourn if they did not return. For every person who came home, there was a lifetime of reckoning their First World War experience, and some found it considerably harder than others to get back to life as they had known it.

Picture the entire street from the records available, and you will see neighbours of every variety. Professional and working class, Church of England and Roman Catholic, born overseas or interstate or locally, and working all across Western Australia in a range of jobs. Some were married with families, and some still lived with their parents. There were larger than life characters scattered up and down Olive Street, and the war affected them in many different ways.

Fathers and Sons: The Durkin Family of 22 Olive Street

Nicholas Durkin was one of the tallest men to enlist from Olive Street, standing over 6’ in height. He was a prospector and miner who worked in some of Western Australia’s most remote outposts, and he was accordingly as rough and ready as you might expect.

In the earlier years of the 20th century, wife Mary Ann had raised their six children, including sons Vincent and Bernard, in the Goldfields centre of Kalgoorlie. During the same time, Nicholas had worked in places as remote as Roebourne and Carnarvon, and his behaviour raised the occasional eyebrow.

In 1910, after the success of a prospecting venture at Bullfinch, Nicholas commenced a six-week celebration comprising “one continual drinking bout”. During this time, Nicholas declared to many fellow guests at the Oddfellows’ Hotel in Fremantle that he and the married proprietor Mrs. Purcell had spent some time in the bedroom together. Mrs. Purcell denied this, and with many witnesses on her side, Nicholas was charged with defamation, and was convicted. The details of the case were widely reported in newspapers around the state.

Mary Ann remained loyal, and the family moved away from the Goldfields and into Olive Street in 1914. When war was declared, Vincent was the first to enlist in 1915, followed shortly after by Bernard. Never one to shy away from adventure, Nicholas wasn’t going to be left behind- he reduced his age by ten years, from 52 to 42, and put his own name down as well.

After many charges of being Absent Without Leave before even departing Australian shores, it must have been clear that military discipline and Nicholas Durkin were not an ideal combination. But it was on arrival in England that Nicholas wasn’t able to complete the basic drills and marches due to his age, and at that, he was discovered, sent home, and discharged. Vincent and Bernard fought out the remainder of the war, and returned home in 1919.

Nicholas died in 1930, aged 67. Bernard married and had a child, but was only 54 when he passed away in 1942. Vincent would later go on to serve in the Second World War, and acted as Secretary of the North-East Fremantle Sub-Branch of the RSL. He is pictured on the left at the 1920 wedding of his sister Fayne (far right), with his future wife Florence Hollins standing behind him.

(Courtesy: Flo Montgomery)

The family’s relationship with housemate George Hunter is unclear. He was a contractor working on a farm in the country town of Wagin, and his wife Ada Allison Myrtle Hunter gave 22 Olive Street as her next of kin address when George enlisted, one day after Vincent Durkin. George was injured a number of times, including one occasion where he slipped off a duckboard and landed on a concealed, upright bayonet, which pierced his foot. Like the other residents of number 22, he survived the fighting and returned home in 1919.

Brothers in Arms: The Rogers Family of 23 Olive Street

Directly across the road from the Durkin home, at 23 Olive Street, the four soldier sons of George and Annie Rogers all enlisted between November 1915 and April 1916. In short order, they were off to the Western Front, ready to do their bit for the war effort. The oldest, miner George, was 24- the youngest, labourer William, only 18.

After enlisting, George married Stella Adella North. Their son, also named George, would be born in his father’s absence- and they would never get to meet. George was killed in action at Passchendaele in 1917, leaving Stella a widow at just 21 years of age.

David Rogers also died a few months later, killed during fierce fighting at Dernancourt. Witnesses said he had gone to the aid of a fallen soldier, only to be struck by a bullet, grenade or shell in the stomach. He was seriously wounded and would not allow anyone to touch him, so had to be left where he was in a position where the German Army would shortly overtake the ground. Many assumed he must have become a prisoner of war, but there was no record of that- he was eventually listed as killed in action after an inquiry.

James Rogers returned home early with gunshot injuries to his hand, while William was also shot in the hand and head, but fought on to the end of the war.

There were many sets of Olive Street brothers who enlisted and fought together, including the three Rankin brothers who lived at 27 Olive Street, a couple of houses up from the Rogers family. Most lost at least one sibling to the fighting.

Luck and Lack Thereof

Wally D'raine was a well-known character around Perth, having been born in the north of England and having come to Western Australia via the United States. He was a successful butcher with several stores, and he approached his work with a salesman's enthusiasm and flair. No publicity was bad publicity for D'raine, who fell out with both his brother and his wife in very public ways.

He was living at 74 Olive Street in 1915 when he enlisted for war, initially becoming a sergeant in the 10th Light Horse Regiment.

Wally D'Raine

Wally also had a combination of luck that was at once terrible and fortunate. He was being treated for bronchitis at the 53rd Casualty Clearing Station near Bailleul in 1917 when an enemy plane dropped a bomb, resulting in serious injuries from shrapnel. After six months of treatment for wounds to his shoulder, chest, face and leg, he was invalided back to Australia and took no further part in the war.

A similar piece of terrible luck befell Ernest Lyndon Menagh, whose brother John Wilson Menagh had lived at 31 Olive Street. A corporal with the 4th Divisional Ammunition Column, he was billeted in a three-storey house near Peronne, and was asleep when an air raid scored a direct hit. He received serious wounds to the legs and abdomen, and died three days later at the 35th Casualty Clearing Station.

Above and Beyond the Call

Three residents of Olive Street were recommended for or awarded medals for bravery during the First World War.

KERRIGAN, Thomas Michael (74 Olive Street)- Military Medal

The Kerrigan family were well-known in the Kulin area, where father John was a local publican. After their son Tom enlisted in 1915, they moved into Olive Street for the remainder of the war years.

At the infamous battle of Pozieres in July 1916, where numerous other Olive Street soldiers were wounded or killed, Tom’s efforts under fire earned him a recommendation for the Military Medal.

At Pozieres from 22nd to 26th July 1916, Pte Claude Tasman JACK and Pte Thomas Michael KERRIGAN continuously carried despatches from Bde Hqs to firing line over country which was continuously swept by heavy machine gun and shrapnel fire. Both men were seriously wounded but sent the despatches which they were carrying at the time back to the Bde Depot Office thus ensuring their ultimate delivery.Tom was wounded during the battle, and much more seriously the following year, when he was shot in the neck. He recovered and returned to Western Australia, where in 1920, John Kerrigan bought the new Kulin Hotel. Tom took over the Billiard Table and Wayside House licenses from his father in 1921, and married Florence Robinson in 1923. He was active in the local RSL in the district, and raised five children with his wife. He died in 1974, aged 80.

GWYTHER, Edward McKinnon (87 Olive Street)- Distinguished Conduct Medal and Military Medal

Edward McKinnon Gwyther was a 19-year-old clerk who had lived in Olive Street and worked in Kalgoorlie, and he was amongst the first to enlist in August 1914. After several bouts of serious illness during the fighting at Gallipoli, he rose through the ranks to become a sergeant. He was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry and devotion to duty at Jeancourt in September 1918, and also recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

On the night 17th/ 18th September 1918 and throughout the operation on 18th Sept. 1918 at JEANCOURT Sgt. GWYTHER and Cpl. JONES were in charge of Brigade and Group Artillery communications and showed great gallantry and devotion to duty in laying and maintaining communications throughout the night previous to the advance and throughout the advance.On his return, he married twice and had children, largely living in the Shenton Park area until his death in 1972.

When our barrage opened the enemy put his barrage down on Group Headquarters, cutting all the artillery and infantry lines. These N.C.Os went out under this barrage and worked for 8 hours mending broken lines, thereby making it possible for communication being kept with the advance, enabling orders to be given to the Artillery and information sent back.

HENDERSON, William John (86 Bagot Road)- Distinguished Conduct Medal

William Henderson was an accountant and legal manager who lived at 86 Bagot Road, on the corner of Olive Street, with his wife Annie. His brother George, a 21-year-old labourer, gave the same address when he enlisted in 1914, and also listed William as his next of kin.

William was an experienced soldier, having previously fought in the Boer War for two years, and his application for a commission with the 10th Light Horse Regiment in 1914 saw him given the rank of Sergeant. He fought at Gallipoli, where in August at the infamous battle of Hill 60, his extraordinary efforts would see him Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

For conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty on the 29th and 30th August, 1915, at Hill 60 (Dardanelles). During the operations Sergeant Henderson rendered most valuable assistance to his Commanding Officer, and when the latter was wounded and ordered away he remained, with one other man only, and successfully held an important section. Finally, when relief arrived, he volunteered to remain, and was in the trench for thirty-seven hours, during which period there was almost incessant hand-to-hand fighting. He proved untiring, and displayed a courage and devotion to duty beyond praise.The Commanding Officer referred to in the citation was Captain Hugo Vivian Throssell, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in the same action.

The story of Henderson's 37-hour hand-to-hand fight to hold a trench is inspiring enough, but his service record reveals that his actions required double the effort. From the moment he arrived in Egypt, he was suffering a recurrence of long-term health problems with his digestive system that saw him taken out of the line multiple times. He had only been back in the line for a brief time from his latest illness when called on to fight at Hill 60. No longer able to digest the field diet, he returned to Australia for change in 1917. But unwilling to remain at home, he went back to Egypt at the end of that year. He saw no further fighting, and returned to Australia again within the month.

William was an active advocate for returned soldiers, and after moving back to his home state of Victoria, became the General/ Federal Secretary of the RSSILA (Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia, later to become the RSL). In 1921, after years of battling the same problems, he was finally too tired to fight on. He died in the No 11 Australian General Hospital in Melbourne in March that year, with his cause of death given as intestinal obstruction and exhaustion.

His brother George, also resident at 86 Bagot Road, was killed in action at Messines in 1917.

A World of Grief at Number 90: the McKinnons and the Sampfords

Though many houses in Olive Street suffered losses, the home at number 90 received a much larger share of bad news than most.

Two different families were associated with the house throughout the war years- first, the McKinnons from 1915- 1916, and then the Sampfords from 1917- 1918.

David Stanley McKinnon in 1915

Annie Catherine “Kit” Fitzgerald married husband David McKinnon, a well-known soccer player for the Caledonian team, after he enlisted in 1915. By the time he departed for war with his brother Daniel, she was expecting their first child.

Tragedy struck early at number 90. Baby David Joseph McKinnon was born in January 1916, and died within a few days. Kit was left to mourn the loss of her baby alone, and her grief would expand in July that year, when David was killed in action at Pozieres. His brother Daniel died one day later in a German Prisoner of War camp of wounds received at Fromelles. The following year, Kit’s closest brother Frank Fitzgerald was also killed in action. On the second anniversary of her husband's death, Kit (by then living around the corner at 82 Bagot Road) placed a newspaper notice mourning all three.

Like the Durkin family at the other end of Olive Street, the Sampfords had a lot of character. Ernest Sampford was a father of seven children between the ages of 9 and 27, and he enlisted with three of his sons to fight.

Arthur was the first son to enlist at the outbreak of war in 1914, and he landed at Gallipoli with the rest of the 11th Battalion. He was seriously wounded within days, with a gunshot wound to the face and an un-united compound fracture of his arm resulting in his return home.

Not long before Arthur arrived back on Australian shores, 21-year-old Charles and 23-year-old Billy enlisted on the same day in July 1915. They fought with the 48th Battalion at Pozieres, where Billy was killed in action. Charles survived the fight, but ran into trouble not long after. While on active duty, he left his post contrary to orders, and at his subsequent court martial was sentenced to ten years of penal servitude. This was commuted to two years of imprisonment with hard labour, but after a year in prison, Charles was released early and returned to the Front. Within weeks, he too was killed in action at Jeancourt.

44-year-old carpenter Ernest was the last to enlist in November 1915, following his sons across to the Western Front. He spent just six days in the field before being urgently removed to hospital with bronchitis and pleurisy. With old age listed as the reason, he was discharged from the AIF and returned to Australia. He later returned to London as a munitions worker for a brief period, before coming back to Australia. He died at the Edward Millen Home in Victoria Park in 1925.

On the Home Front

From 139 Barker Road, enthusiastic volunteer Arthur Tyrrell Williams went to Gallipoli with the 10th Light Horse Regiment. But in 1915, he was wounded in action and forced to return to Australia. On the home front, he became a fervent campaigner for recruitment in Western Australia, speaking at rallies and even writing a patriotic song, The Gallant Light Horse, with his pianist wife Nellie.

The Gallant Light Horse, by Williams and Williams

Arthur was not just a man of words. He was also prominent in working to assist returned servicemen, becoming Western Australia’s secretary of the RSSILA (RSL), and proposing a settlement scheme for the Riverton area. When that failed, he commenced a business in which wounded soldiers made and distributed sandwiches to offices in central Perth.

Beyond the War

Many Olive Street soldiers had a difficult time after their return from war. Some were arrested for public drunkenness, abusive language, and running betting operations. Others were divorced or separated, or charged with the maintenance of illegitimate children. Many of those who made it home died far too young, within a decade of their return.

Amidst the difficulties, there was also hope. Widows like Stella Rogers remarried and began new families. New careers began for many whose physical capacity had been altered by their war experiences, and some achieved great success.